Staying effective in different weather conditions

Staying effective in different weather conditions

How do you avoid soaking your winter clothes with sweat? Is there anything you can do to relieve yourself in the summer heat? Are freezing toes and fingers in the cold a personal thing that can't be helped? What to do if you fall into the water in the winter and only some spare clothes remain dry? Can you increase or decrease body heat by eating or drinking?

This is the longer and more in-depth one of our articles on this subject. Click here if you want to learn the basics of dressing in layers and what clothes to purchase.

Foreword

On avoiding hypothermia, heat paralysis, and everything in between.

A comfortable feeling (or "individual combat readiness" in fancy soldier terms) depends on many things. One component of this is layered clothing, but the subject is far wider than just baselayers, mid-layers, and shell garments. Over the years, we have published several articles and guides about surviving the cold, using your clothing layers, and so on. Now it's time to bring this convoluted mess into one definitive package.

This article should be useful to anyone, anywhere. That means You, too. It doesn't matter if you're performance-oriented, serving in the military, or just someone who steps outside sometimes. Everyone can benefit from understanding how their body functions and how to retain and improve that functionality. Or just comfort. There's no shame in being a bit self-indulgent: even a good soldier will rest, eat and drink when possible to be at their strongest when the mission requires.

We'll cover general principles and basics followed by simple, practical examples and tips. By applying these, you can come up with solutions of your own, which is the purpose! Nurture your understanding of why clothes have certain features and how your body works in various situations.

With these teachings, you don't have to learn a long list of "do this, put that on"-rules. Instead, you can recognize what's happening, prepare for things in advance, and solve unexpected situations on your own.

- Basics of Heat Transfer

- Handling the Elements With Clothing and Action

- Operating in a Cold Environment

- Operating in a Warm Environment

- Thoughts on Clothing and Equipment

1. Basics of heat transfer

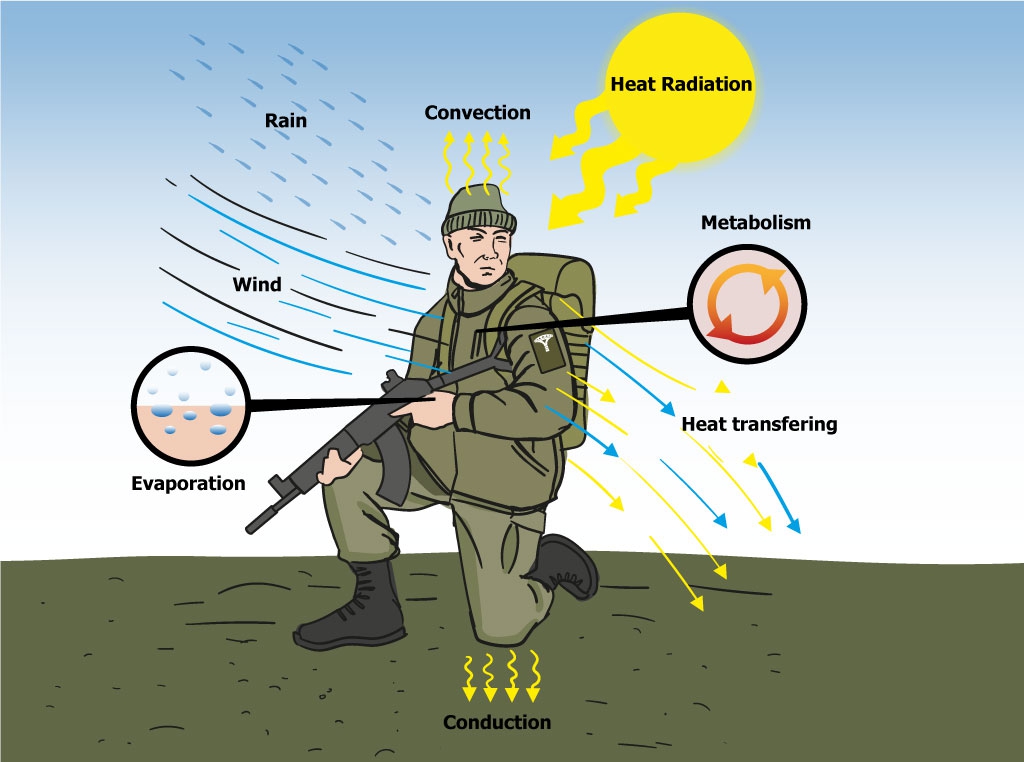

Heat energy transfers between substances from hot to cold, to reach equilibrium. The greater the temperature difference is, the faster the process is. Roughly speaking, five things transfer heat from (or to) your body, three of which are the basic processes of transmitting heat and their applications are the final two - pay attention, this is theory that will help you later in practice.

1.1 Conduction

The simplest examples of conduction are when you grab a cold door handle or a hot cup of coffee and heat energy is transferred to the colder material. Heat is also conducted from the skin to the surrounding air (or vice versa). All materials conduct heat, be they in a liquid, gaseous, or solid form.

Air is a fairly poor conductor of heat, water on the other hand conducts heat quite well. Putting your hand into an empty sink doesn't feel like anything, but if the sink is full of room-temperature water, it'll feel cool. This is why clothes that trap air are good insulators and wet clothes conduct heat away from you.

1.2 Convection

Convection means that a flowing gas or fluid carries heat along with it. For example, when the skin has conducted heat to the air next to it, the warmed-up air rises and is replaced by cooler air. Convection can be forced by replacing the air more quickly, e.g. when the wind blows or a cyclist rides through the air. The effect can be easily noticed and the cure is quite simple: windproof clothing.

Folks living in colder regions and sailors know just how much Wind Chill can rob your body heat and make just a cool day a freezing one. The wind is a significant booster of the cold and conversely offers effective relief from the heat.

The blood circulation is also a form of forced convection: warm blood from your muscles and internal organs flows in your veins and carries heat to your extremities and close to the skin, where it conducts the heat energy to the surrounding body tissue.

1.3 Heat radiation

Radiation is the least significant of the three when it comes to losing body heat but survival blankets often have a reflective surface to improve the odds. If you must build a fire in an emergency, prop something like a tarp behind you to reflect the heat back to your body. In military applications, masking your heat signature is an important aspect of being more difficult to detect with thermal surveillance. Heat radiation reflects and appears to these devices just like the light we see with the naked eye.

Despite not losing lots of heat through radiation, the body can be exposed to large amounts of radiation from the sun. Understanding how it works is crucial whether you're in the freezing cold, or scorching hot desert.

1.4 SWEATING

The human body has ways to remove excess heat, sweating is one of them. Sweat transfers heat to the surface of the skin by convection.

1.5 EVAPORATION

When the surface of the skin is covered with sweat or a wet piece of clothing, the body heat is conducted to it. As the liquid evaporates i.e. changes into a gas, the process cools down the remaining liquid. This accelerates the loss of heat energy, which can be a good or bad thing, depending on the situation.

Cotton underwear is a poor choice for this reason: cotton absorbs and binds moisture inside as well as in between the fibers. The amount of moisture is large and takes a long time to evaporate, all the while conducting heat.

Synthetic moisture-wicking materials are almost the exact opposite of cotton. They soak no moisture at all but bind it in between the fibers due to capillary action. Even a small droplet of sweat spreads out to a larger surface area and evaporates quickly.

Wool fibers soak only a small amount of moisture and ordinary wool isn't eager to bind it. Merino wool fibers are much longer and finer and capillary action can once again be observed.

2. Handling the elements with clothing and action

Our survival and comfort outdoors is comprised of three factors: the forces of nature, your actions, and clothing including accessories, footwear, and so on. If you balance your clothing and action (anything that accelerates your metabolism) with the conditions, you can "trick" your body into a nice sense of balance where you don't sweat, but blood flow is not restricted from the extremities, either. This means a comfortable feeling where you're not pouring sweat or freezing your toes off. Because your body reacts to what is already happening, act in advance i.e. reduce your clothes before increasing physical effort.

2.1 THE ELEMENTS

The elements such as temperature, air humidity, and wind can't be changed, but you can adapt to them. They can rob you of heat or burden you with excess heat - even more effectively when combined (moist and windy weather, for example). In addition to moving and wearing clothes, you can protect yourself from exposure by going into a shade, rain cover, or wind shelter.

2.2 YOUR ACTIVITY

You can affect your metabolic rate by various means but sometimes you must move to get from one place to another – or stay still. Activating the body produces heat. The body reacts to heat by increasing the circulation closer to the surface, and to the cold by restricting blood flow everywhere except the head and torso; the vital organs.

If you're into numbers and such, here's a chart of metabolic rates, which in this case isn't about losing weight but producing heat. The unit Met describes heat production per body surface area so that 1 Met is defined as 58 Watts / square meter, which is roughly the metabolic rate of a person sitting relaxed. The surface area of a human is set to 1.8 m2. Below are a few examples:

| Sleep | 0.8 Met |

| Seated position, relaxed | 1.0 Met |

| Standing, light moving around | 1.6 Met |

| Raking leaves | 2.9 Met |

| Walking over flat lands 5 km/h | 3.4 Met |

| Riding a bike 15 km/h | 4.0 Met |

| Running 15 km/h | 9.5 Met |

2.3 CLOTHING

What you wear is the easiest of the three to adjust, especially if you had the foresight to pack the right stuff with you. Clothes provide insulation and protection from the elements but can also be used the other way around: to help your body get rid of excess heat and protect from the sun's radiation.

And guess what, there are numeric estimates of these, too! The unit Clo describes the insulation properties of clothes with 1 Clo defined as an ensemble of clothes enough to keep a sitting person comfortable at room temperature without significant effects of wind or moisture applied.

A few examples* of Clo-values of pieces of clothing and accessories:

| Briefs | 0.04 Clo |

| Long Johns | 0.15 Clo |

| T-Shirt | 0.08 Clo |

| Undershirt w. long sleeves | 0.2 Clo |

| Light shirt | 0.2 Clo |

| Flannel shirt | 0.34 Clo |

| Normal pants | 0.24 Clo |

| Thick knee socks | 0.06 Clo |

You can make estimates by adding up the value of each piece. In practice, clothes often insulate more than the sum of their values. Apply common sense: wearing four light jackets and nothing else isn't going to work well.

Material and fit affect how all clothes work. For example, the baselayer should be against the skin to be effective. A loose jacket allows you to wear insulating layers, but without those in place, convection can allow warm air to escape a baggy jacket more quickly than a properly fitted one.

2.4 A bit of math

Examples** of the insulating values of clothing ensembles:

| Nekkid body | 0 Clo |

| Light summer clothes | 0.6 Clo |

| Winter outdoor clothing | 2.0 Clo |

| Heavy winter clothing | 4.0 Clo |

The equation of producing and losing heat can be expressed like so:

M-W = K+C+R+E+S

- M: Metabolic rate

- W: Work

- K: Conduction

- C: Convection

- R: Radiation

- E: Evaporation

- S: Stored heat

Are you lost at this point? Let's recap with the focus on the important stuff:

- Metabolism produces heat

- You lose the most heat through conduction and convection

- Moisture increases conduction, the wind increases convection

- Evaporation convects heat away and also cools down the surface.

*Source: ASHRAE Handbook, ASHRAE, Inc., Atlanta, GA, 2005.

**Source: Notes for course "Human Factors: Ambient Environment", Prof. Alan Hedge, Cornell University, 2013.

3. Operating in a cold environment

Avoid the rookie mistake of wearing too much. In about 15 minutes from starting to move, your heat production and circulation are up and running. Being cold in the beginning is a good sign to look for, and it's always nice to add something if necessary. Removing clothes after you've started to sweat is extremely dissatisfying. Do some warming up indoors before going out to cheat some comfort in your life. Breaks will cool you down quickly, so make sure you have easy access to a thicker jacket, maybe pants too.

Are you the kind of person who wants to climb the hill ahead to "earn" the break? Food for thought: it might be better to use the cover of the hill for resting before starting the climb. You will have fresh legs for the climb, and it will get your heartbeat back up after the break.

The emphasis on quick drying is a two-bladed sword in the cold: the moisture bound between synthetic fibers evaporates quickly and feels cold. Wool is not as aggressive in this regard, and that's part of why it feels comfortable when a bit wet.

Not getting your clothes wet in the first place is by far the best option you should aim for. After donning the right clothes in the right order, you can fine-tune them as follows: zipping up the collar and tightening the cuff tabs reduces convection from within your jacket. The hem is also a large opening for losing heat, this is where an adjustable waist is useful. All of these work the other way around: by opening the collar and doffing the beanie you can quickly dump excess heat. You can also close the jacket with just the buttons or snap-ons to combine protection and ventilation, and most shell jackets have "pit zips" below the arms.

3.1 COLD AND DRY AIR

In freezing temperatures, the air and environment are often relatively dry, which makes things less of a challenge. Also, it doesn't rain all the time during spring and fall. This makes the choice of clothing easier, as you don't need to worry about waterproofing. The wind and sun play a large part so keep these in mind.

If any part of your body feels conspicuously cold, remember the circulation: your gloves and boots may be good but your torso is losing heat, causing the blood to cool down before reaching the fingertips. In some cases, a vest can be the best thing to make your fingers warmer, even though it's not worn even close to the hands. On the other hand, if your back is sweaty while your toes are going numb, swallow your pride and don the Long Johns. Your thighs have large muscles, lots of circulation, and quite a bit of surface area: all factors that increase heat transfer.

A tip for bicycle winter riding: the cooling effect of zipping through the cold air stops as soon as you arrive to wherever you were going but your internal heat generator still runs for a moment. Take the shell jacket and headgear off immediately, even before locking your bike, to avoid post-sweating!

The comfort of your toes and fingers is not only about what you wear over other parts of your body. Tight-fitting gloves and shoes don't insulate as well as more generous mittens and boots. At worst, your circulation can be restricted due to tight footwear, at the very least wool socks are compressed and offer less insulation.

3.2 COLD AND RAINY WEATHER

It's difficult to imagine weather more difficult than cold and wet. When you're still, it's easy to put on warm insulating layers and a waterproof shell, but if you must move briskly, you'll be facing choices.

Waterproof membranes become less effective in the cold, even if you think they don't work that well in the first place. The reason is rather simple: waterproof and breathable membranes rely on microscopic pores that are too small to let water molecules through in liquid form, but they do let steam (gaseous water) through. Sweat evaporating from your skin and moisture-wicking baselayer can condense to the inside of the cold shell, soaking your insulating layers. Bummer! If you produce enough sweat and heat to warm up the shell to the point where it works better, you are unlikely to feel good.

You can decrease sweating by wearing less in the first place. Often just a baselayer and shell garments are enough, sometimes even these are too much. Luckily, these clothes don't rely entirely on the promised breathability, but have proper ventilation as well. In this kind of conditions, they are indispensable. If you find it necessary to add layers, consider wearing them over your shell jacket to keep the breathable membrane closer to your body where it should work better.

Do you have a moment to talk about rain ponchos? They are waterproof but also incredibly well ventilated due to being open at the bottom. Depending on the length, they may cover even the knees - at the very least your thighs and butt are covered. Draping the front over the handlebar on a bike keeps your pants dry from the knees up, just tie the hem or tail to avoid fluttering. Rain ponchos also allow your clothes to dry in case they got wet.

Everyone who moves in the cold and wet will get wet at some point, no matter how skilled they are. The equation may be simply impossible: either you get wet from the rain or your sweat, or both. As long as your clothes don't hinder your movement despite being wet, and you don't lose too much body heat, you're good. In the end, your skin is waterproof. The insulating layers made from synthetics or wool don't stop working entirely even when wet, they just don't work as well. In any case, it's a good idea to keep a spare insulating layer with you in a drybag, in case other means fail.

If you fall into the water, the biggest danger is defeated once you get on solid ground. Squeeze excess water from your clothes - especially synthetics won't have lots in the first place - put them back on and start moving. If you can't leave the place, walk in circles, do squats and jump around. Avoid closing your wet clothes into a shell where they would take longer to dry. Instead, let off steam as much as possible. Again, it may be a good idea to wear your shell jacket and pants close to the body to keep moisture off your skin, have steam go through the membrane and then go through the outer layers without obstruction.

3.3 NUTRITION AND HYDRATION IN THE COLD

Here's a real joke: eating ice cream warms you up. Even though it's cold, it's a fatty energy bomb, and metabolizing it produces lots of heat. If you're in a situation where you must consider your body heat in relation to what you eat, choose high-energy foods and avoid vegetables, especially ones that contain lots of water, such as cucumber.

Spicy foods make you feel warm and may even make you sweat, but this isn't a matter of producing more heat. It just comes to the surface. The same thing is true for alcohol: a few sips of whisky to warm you up expands the veins and makes you blush a bit but it only makes you colder in the long run. It's like peeing in your pants to keep you warm. Speaking of pee...

The body reacts to cold by increasing the need to pee. Also, breathing cold and dry air dehydrates you slightly more than normal. When you consider the burden of thicker clothing and possibly a more difficult terrain due to snow, dehydration is an actual risk during the winter. So remember to drink water, "hydrate", as people say to sound important. Oh, by the way, coffee is allowed. The diuretic effect doesn't cause more free water loss compared to the fluids you get from the cup of warm brew.

4. Operating in a warm environment

Many guides to the outdoors and layered clothing focus on cold environments. The effects of heat and ways to mitigate them are rarely covered in depth. Even if you live in a temperate zone, it's likely that you will benefit from putting some effort and thought into your hot weather wardrobe as well.

Air convection is effective in hot weather if you only let it happen. Use loose clothes, leave the sleeve cuffs and collar unrestricted and the hem untucked. So precisely the opposite of what you would do in the cold to prevent heat loss.

4.1 ARID ENVIRONMENTS

"Yeah, man. But this is dry heat!"

As the sun shines, the environment often has cooler spots where its rays haven't yet reached. If the situation allows, use these for moving and breaks. Where a natural shelter isn't found, you can pitch a tarp to give you shade.

While shorts and a T-shirt are tempting, radiation from the sun is harmful for two reasons: it heats you up and the UV radiation damages your skin. There's only so much vitamin D you need. As counter-intuitive as it may sound, long sleeves rolled down and long pants together with a boonie hat are the healthiest choice. The body can often regulate and maintain a suitable micro-climate underneath these without further arcane tricks.

If the temperature is high and you must get moving, active cooling measures may be useful. Again, keep the circulation in mind: blood carries heat energy. Could it work like a liquid-cooled motorcycle or car engine? It not only can but also does! What's was that inferior fabric again that soaks moisture and dries slowly? Oh yeah, it's cotton.

A wet cotton scarf on the head or around the neck is a very effective measure to get rid of excess heat. It's not only the conduction at work here, but the evaporation process actively cools down the remaining moisture in the scarf. The material is not that important, wet Merino wool will "suffice" if you have nothing else.

4.2 HOT AND HUMID

Everyone has sometimes gotten wet in the summer rain and noticed it wasn't that bad. The feeling points in the right direction: being wet isn't the end of the world in itself, and it'll be dry soon enough. Be prepared with dry clothes for breaks and rest, though.

Very high temperatures and moist air is worse than dry heat. This effect is described as The Heat Index. It can be a dangerous combination, like a sauna with no way out.

If you paid attention in the theory section, evaporation slows down when the surrounding humidity is higher. Slow-drying, heavy cotton isn't good at this point, switch to mixed or synthetic scarves for better results.

Convection can help a lot. If the wind doesn't blow, large leaves or a fan helps to move the air. At home, electric fans are good even without AC function, just get the air to move over your skin.

4.3 Summertime nutrition and hydration

It's not a coincidence that spicy foods are popular in temperate and hot zones. They accelerate sweating even if you aren't moving, which cools down your body. You can slow down your metabolism somewhat with vegetables containing lots of water, such as cucumber.

Here's another joke you shouldn't laugh at: leave cold drinks to parties. They feel good in the mouth but your body will actively work to warm it up in your stomach. Work produces heat. Tap water (if it's potable) should only be used at the cold setting but you can let it warm up before drinking. At home, you can keep a can of water on the table, and on the move, drinking bottles, canteens, and hydration bladders should be kept ready.

5. Thoughts on clothing and equipment

5.1 Baselayers

Everything you wear next to the skin is among the most important component of layered clothing, even though shell jackets get all the attention with their details about water pillars and vapor permeability. A proper baselayer gets better you through unexpected situations and can even compensate for less ideal clothes worn on them.

It doesn't make sense to have too much insulation directly on the skin. These clothes should wick moisture and slow down the convection of air right at the skin. In a way, the baselayer does what your skin attempts to feebly achieve with goosebumps.

Mesh or rather netted underwear are very effective breathers and keep the next layer - which might be just the shell jacket - comfortably off the skin, without being too hot despite the thickness. They are also durable and easy to repair.

Just a T-shirt and boxers count as the baselayer in warm conditions. Surprisingly soon below room temperature, covering your arms and legs becomes a smart move. In very cold environments, the baselayer may be a little bit thicker as you are unlikely to need the thinnest option possible.

5.2 Midlayers

As the name implies, these go between the baselayer and shell. The amount of midlayers starts from zero and goes up to about "several". A minimalistic midlayer can simply be another baselayer on top of the other, perhaps in thicker form.

The purpose of midlayers is to bind air between the body and environment to prevent conduction and convection from scrounging your precious body heat. Other than that, the functionality is defined by what these clothes must not do: soak moisture, sweat, weigh.

Donning and doffing midlayers can be cumbersome, so think carefully about the level of insulation you add here. Leave a little room for dumping heat if required. If you're concerned about getting cold when you take a break, consider separate clothes for those situations instead. A loose-fitting midlayer jacket can serve as an overgarment for breaks as well!

Just a plain old woolly pully is a good example of what to wear, even though it's not as lightweight and packable as modern thermal jackets and pants - which are a lot like sleeping bags with sleeves. The rib-knit of the British army jumper has lands and grooves to help insulate the wearer without being thick all over. Wool shirts breathe really well, which you can notice as a lack of protection from the wind. Just opening the jacket allows you to cool down quickly.

5.3 Shell jackets

People are so fixated on shell jackets that they should have an article of their own. The markets smell the cash and feed the hungry consumers with details about laminated materials, water and vapor numbers, and wavy arrows. Enthusiasts play along and the subjective choice is obviously superior.

When your base- and midlayers are good, the shell jacket is not really that important in the end. It should block the wind and some rain and be hard-wearing. It's a bouncer that keeps unwanted guests out but what about the excess heat and moisture trying to get out? At that point the bouncer should politely step aside and open the door.

The demands are conflicting. Usually, breathability is the more important factor. Proper rainwear is better for heavy rain. In addition to having the material itself breathe, adjustments to fit and vent the jacket to regulate your temperature are very useful.

In fact, many army jackets work very well as a shell jacket. They have had the appropriate features for decades. (This is not a coincidence.)

5.4 Headwear and scarves

The head and neck are effective areas to dump excess heat. Conversely, a scarf around the neck is an important component of staying warm. The collar allows warm air to escape (convection), and the neck has a lot of circulation to carry and lose body heat.

You can apply layered clothing to the head and neck like any other part of the body. Wearing a merino wool balaclava or liner beanie may allow you to wear your summer hat during winter. This approach is adjustable instead of the "all or nothing" you get with a single winter hat.

5.5 Lofty jackets and pants

A warm jacket to wear on breaks is a splendid thing to have and worth the cost and weight. Choose light and packable ones so you are more likely to use them: something stuffed into the main compartment of your pack is usually something you need 1–2 times in a day.

Waterproof and durable shells can make these too thick. Settle for water-resistant exteriors and look for similar materials as used in sleeping bags. You can use these as midlayers, saving weight and bulk thru multi-purposing.

The jacket should have snug cuffs, a high collar, and an adjustable hem. Synthetics aren't as packable as down but they are hydrophobic so the choice in damp conditions is clear.

Long side zippers help donning and doffing the pants without taking off your boots.

5.6 Footwear

This is a too large topic to be covered in general, but here are some thoughts relevant to this article.

Many people think they have magic footwear that fit well in the summer and have room for a wool sock during the winter. This is obviously not the case: if the boot really fits well, a wool sock is compressed, making it less airy i.e. insulating. Not to mention the reduction of circulation, so warm blood doesn't get where you want it to go. Third, heat from your feet is conducted through the boots into the cold ground so a thick felt insole might be useful. For winter use, do get large enough boots to ensure you have room for circulation and insulation! And don't overtighten those laces.

In the summer, too many people incubate their feet inside "breathable" membranes, as if the rain or stepping into the puddle is a constant danger. And once you step into a river stream or bog, it takes ages to get anything dry on your feet. Membranes have their uses in footwear but rubber boots are better for constant submerging and plain leather boots are enough protection most of the other times. Ask yourself, do your daily shoes really have to be waterproof?

5.7 Gloves

Contradicting requirements don't give you a break: you need warm and durable gloves, but you should also be able to manipulate buttons and levers while wearing them.

Layering principles help solve the problem. The first step towards warmer hands is wearing the same gloves but one size larger. This reduces straight-up conduction thru the glove, so it's already better on its own but can also be worn with a liner glove. Gloves can easily get wet but separate ones dry faster.

It's OK to wear gloves under mittens, despite the separate fingers usually being the colder option. A mitten encloses all fingers and takes care of insulation for the most part, as it has a smaller heat-losing surface area. This pretty much eliminates the heatsink fin effect of separate fingers.

5.8 Other gear

Clothes are not the only thing in the way of heat escaping the body. A pack on your back covers a large area and insulates quite well, but breathability is poor. Protective and load-carrying gear have pretty much the same effect, save for the small areas that may have mesh. Yippee. Also, all the weight you carry increases your metabolic rate unless you have mag pouches that walk on their own.

You can use this to your benefit by using your backpack (or a sitting pad) as a seat to keep your ass off the cold ground. Most often, however, everything you carry is a burden you can only compensate for by wearing fewer and lighter layers. Life is much better when wearing a good undershirt. Also, grab any chance you get to lighten your load.

OUTRO

Give serious discomfort a try. You can learn to tolerate it and through mistakes (deliberate or otherwise) you can learn to avoid or survive various situations. When the stakes matter, though, take good care of yourself. I hope this article helps you achieve that.

-Sauli

The author has spent a lot of time in various environments: in military service from the Mediterranean Balkans to the snowy fjords of subarctic Norway, and life adventures in East and Southeast Asia. For the past ten years, he has made his way to work on a bicycle around the year in Helsinki.